Advocating Messy History

Beyond the specific cases of Monotype and Linotype, our research suggests that a number of type manufacturers in Europe and in the USA employed women who actively contributed to the design, development, and production of many typefaces throughout the twentieth century. Such contributions have proved difficult to document, as many of these workers entered the type industry only for a few years before moving on, either to have a family or to take on other (often non-type-related) employment.

Moreover, many of the women we have managed to trace do not seem to recognize the value of their contributions and do not see the point in reflecting on their experiences. This may partially explain the invisibility of women in current narratives of design history. As Martha Scotford, professor of graphic design, stated:

For the contributions of women in graphic design to be discovered and understood, their different experiences and roles within the patriarchal and capitalist framework they share with men, and their choices and experiences within a female framework, must be acknowledged and explored.

Scotford also introduced the concept of ‘Messy history’, which has been driving us throughout our research:

Neat history (conventional history) involves the simple packaging of one designer, explicit organizational context, one client, simple statements of intent, one design solution, a clearly defined audience, expected response...

Contrast this with messy history: designers who do not work alone but in changing collaborations; design works that are not produced for national or large institutions but for small enterprises or local causes.

View of the Monotype Works, undated photograph. © Monotype Archives

International Photon Corporation letter drawing studio in Paris, 1970s. Courtesy Musée de l'Imprimerie et de la Communication Graphique

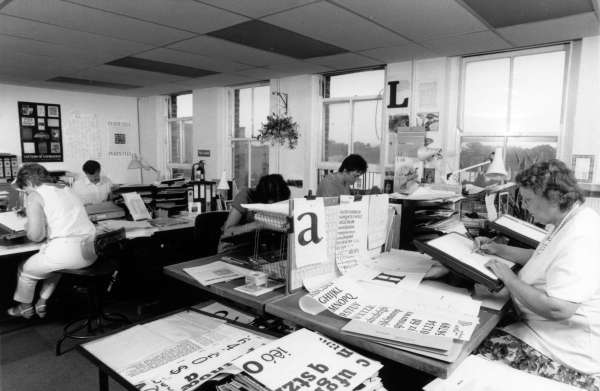

View of the Monotype Type Drawing Office in the 1980s. © Monotype Archives